By Preston Russell

Have you ever asked, “When did these 27 books at the end of my Bible get grouped together?” Were they always grouped together? If not, what is the story of how this happened?” You may be surprised that it took time for the church to recognize these 27 books, and only these 27 books, to make up her New Testament canon: her authoritative, God-breathed New Testament witness to Jesus Christ, as proclaimed by his apostles. To be sure, the church all over the place recognized most of the books of the New Testament from a really early time (the four Gospels, Acts, most, if not all, of Paul’s letters, 1 Peter, and 1 John). This is an amazing reality in itself! In other words, a “clear core” sprung up early. However, the edges of the NT canon were not solidified until about the 4th century or the beginning of the 5th century AD. Some churches put some books at or near the level of the core books that would not be accepted later. Other books that would be accepted later were initially seen with an eye of suspicion. In other words, until the 4th or 5th century, the New Testament could be described as having a “clear core” with “fuzzy fringes.”

Where do we learn about this history? Mainly from early church leaders who lived during this crucial time and ancient lists of sacred Christian books. But here’s the kicker, which is also the focus of this blog post: New Testament manuscripts reflect this story of the church recognizing her Scriptures.

My goal in this post is not to give you a well-rounded and thorough education on the relationship between New Testament manuscripts and the canon. A blog post is a poor place to do that! Instead, my goal is to whet your appetite to learn about the origins of Christianity and the place that New Testament manuscripts have in this story. Check out a few fascinating ways New Testament manuscripts reflect the story:

Markings in manuscripts can tell us how they were used.

As I just mentioned, a lot of the books of the New Testament were recognized as having Scriptural status, at least on par with the Old Testament, at a surprisingly early time. Let’s flesh this out a bit for the Gospels, for example. As early as the mid-100s AD, there was a Christian apologist by the name of Justin who was writing the earliest description of a Christian worship service that we know of. Listen to what he says:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles [in other words, the Gospels] or the writings of the prophets [in other words, the Old Testament] are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things.[1]

What does Justin tell us? He tells us that the Gospels were already put at least on the same par as the Old Testament Scriptures in churches that Justin knew about just a few decades after they were penned. As if this quote wasn’t fascinating enough, the earliest New Testament manuscripts of the Gospels reflect what Justin is saying.

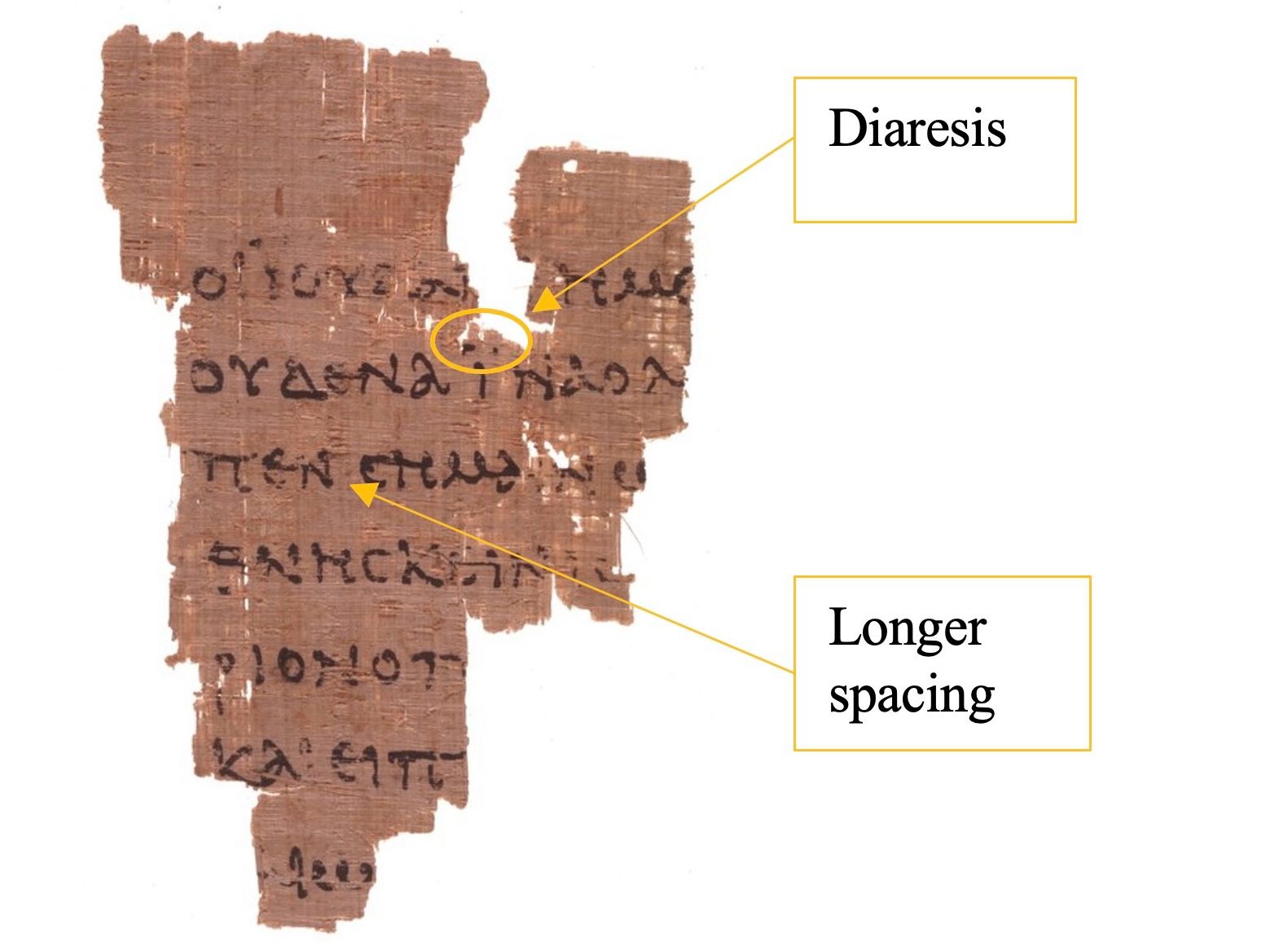

Look at P52, for example. This famous credit card-sized fragment of John’s Gospel could well be the earliest New Testament manuscript that we know is still in existence, dating somewhere within the 100s-200s AD. And although it is such a small scrap of papyrus, it tells us that it was likely used for public reading in Christian worship gatherings, just by a couple of key markings: Two dots over certain vowels (diaresis) and larger spaces probably helped readers as they publicly read in the worshipping assembly. In other words, P52 likely reflects what Justin said about the Gospels being read in the early Christian worship service.[2]

Hebrews in the Pauline letters

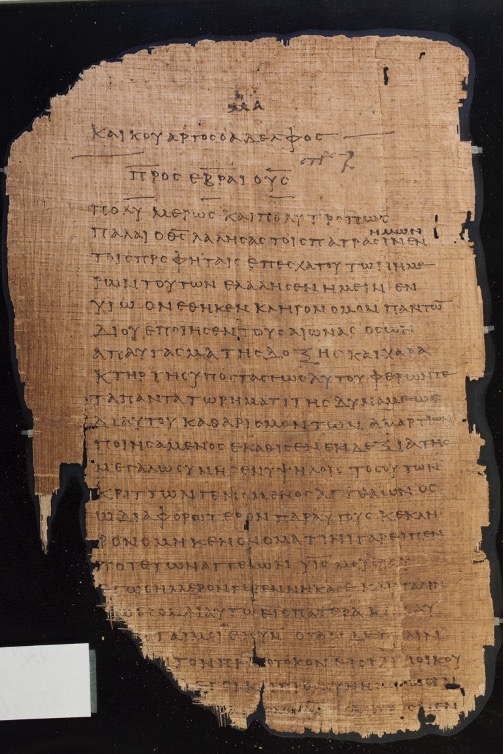

The book of Hebrews had a tough time being widely recognized as New Testament Scripture. It seems like the reason for this is that the book does not say who wrote it. The early church struggled with this. Was it an apostle? Was it not? Several early church leaders came to believe that the apostle Paul wrote it, and this belief is likely what moved more of the church to regard it as part of the New Testament, and eventually become an established part of the New Testament collection of writings. Again, this belief is reflected in the earliest manuscript of Paul’s letters, 2nd-3rd-century P46. Right between Romans and 1 Corinthians, we find Hebrews, placed as if there were nothing unusual about its part of the codex.

Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Alexandrinus, and the “fuzzy fringes” of the canon

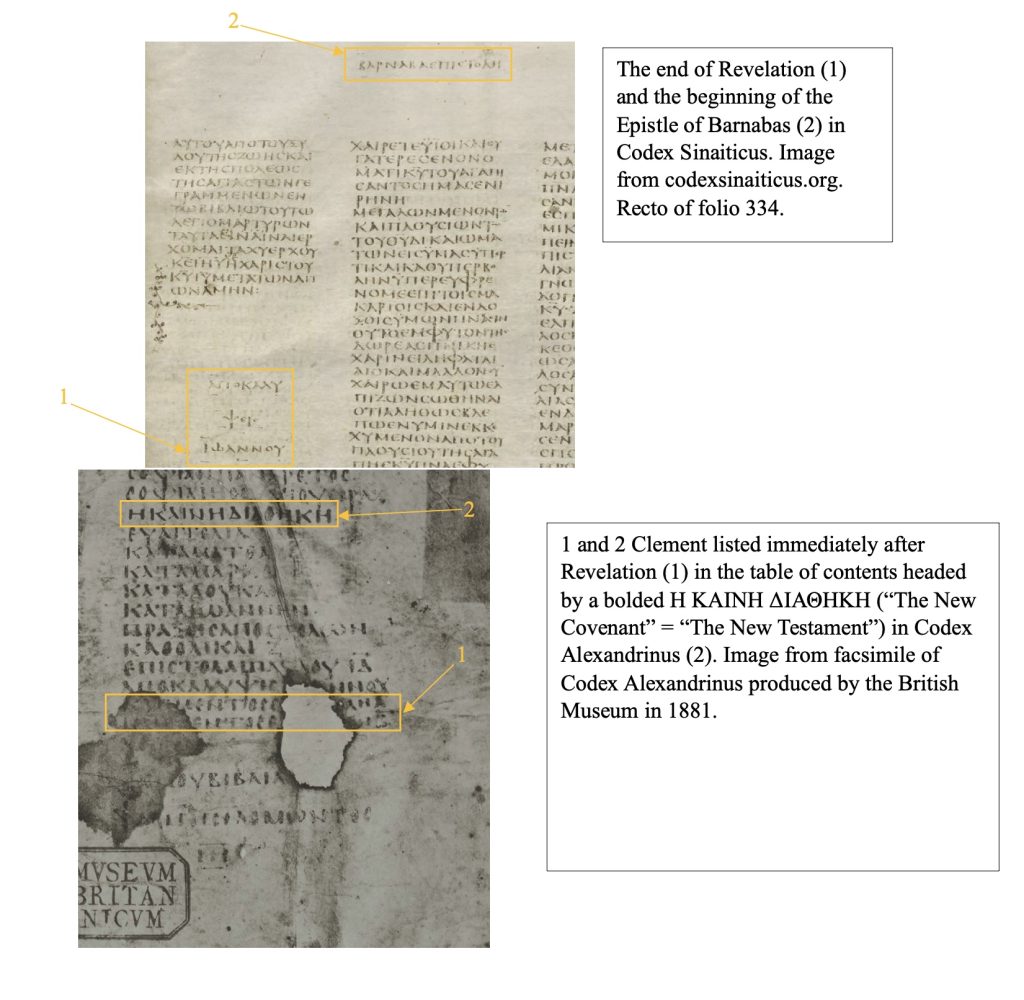

Two of the most important New Testament manuscripts are 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus and 5th-century Codex Alexandrinus. As you can read about in our post on the contents of New Testament manuscripts, both of these codices include a couple of books that are not part of our 27-book New Testament: Codex Sinaiticus has the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas, and Codex Alexandrinus has 1 and 2 Clement. Both codices place these books after Revelation. What do we make of this? For starters, each of these four books factor into the “fuzzy fringes” of the New Testament canon: They were books that were more-or-less put into the same conversation with other New Testament books here and there. So does this mean that codices Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus see these writings as on par with the other New Testament Scriptures? Some scholars say yes, while others say no. The point here is that these New Testament manuscripts reflect not only the “clear core,” but the “fuzzy fringes” of the New Testament canon.

So much more could be said about manuscripts and the New Testament canon. And, thankfully, more has been said! Check out the Recommended Resources below to jump further into this field. As you have seen from just a few examples, New Testament manuscripts play a really important role in helping us understand the story of how the New Testament came to be as the collection of 27 books in your Bible. And that is just one more way that our work at CSNTM is underscored: Making top-quality New Testament manuscript images not only preserves these priceless treasures, it also sheds invaluable light upon the foundations of Christianity.

Further reading:

Larry Hurtado. “The New Testament in the Second Century: Text, Collections and Canon.” Chapter 1 in Transmission and Reception: New Testament Text-Critical and Exegetical Studies. Text and Studies, 3rd Series: Volume 4. Edited by J. W. Childers and D. C. Parker. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006.

John D. Meade. “Myths about Canon: What the Codex Can and Can’t Tell Us.” Chapter 13 in Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism. Edited by Elijah Hixson and Peter J. Gurry. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2018.

Bruce M. Metzger. The Canon of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987.

Eusebius of Caesarea. Ecclesiastical History. Book 3.

Edmon L. Gallagher and John D. Meade. The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

[1] From ANF 1:185.

[2] Hurtado, 11.