By: Preston Russell

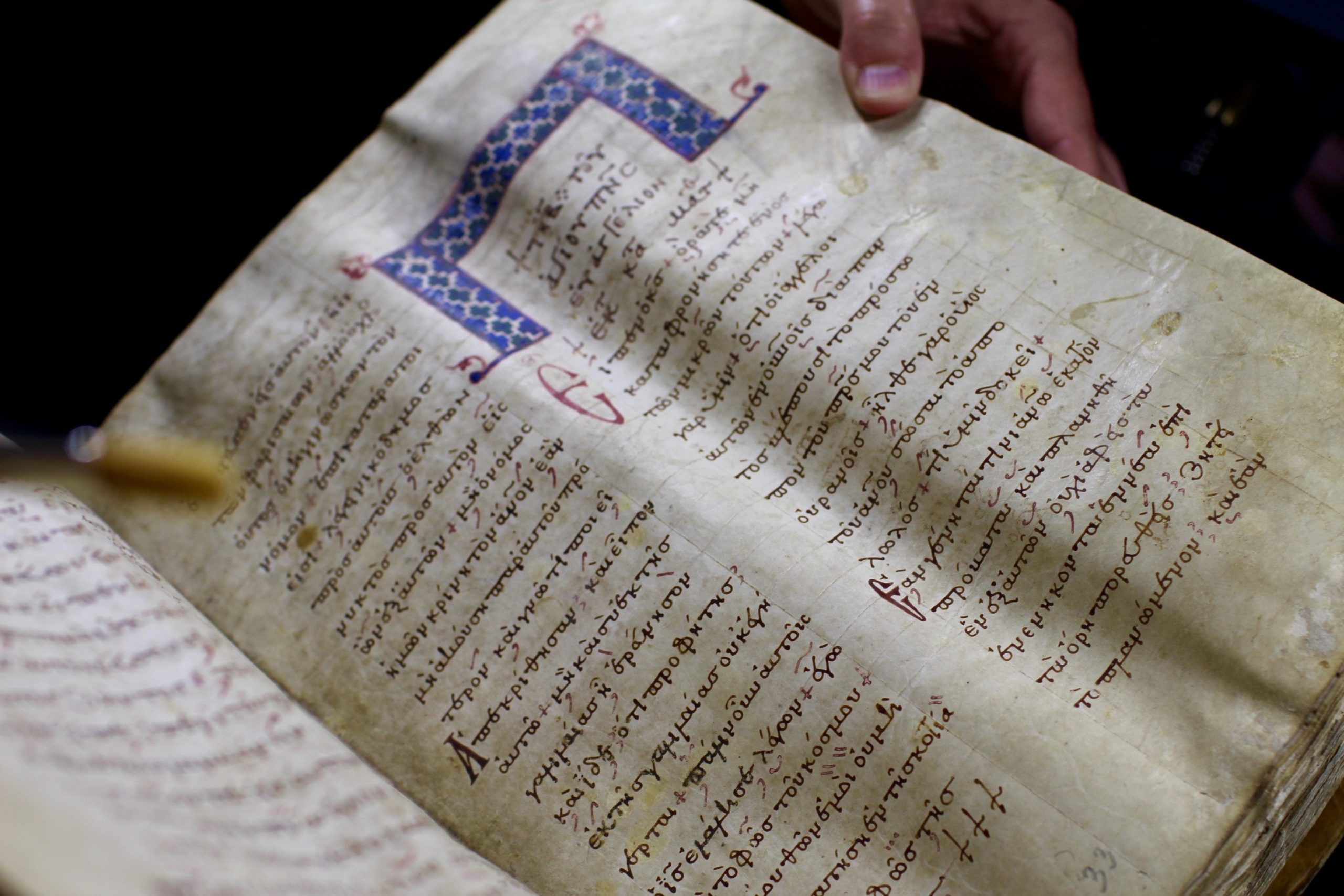

Have you ever cracked open a New Testament and wondered, “How did this 2,000-year-old book get to the point that it is now sitting in my lap?” You may think, “Ancient New Testament manuscripts have something to do with it, no doubt. The scribes who copied them surely played a part, too. And, of course, there are those Bible scholars and translators that somehow get from manuscripts and scribes to this New Testament in my hands.” But you may be surprised to find out that an important piece to this puzzle is an ancient collection of writings that is not the New Testament. I am talking about that broad collection of works that scholars call Patristic writings. These ancient and fascinating works written by early leaders of the Church shed a remarkable amount of light on the text of the New Testament. Although many paragraphs could be easily spent delving into the various ways these ancient pastors, scholars, and theologians help us in the work of New Testament textual criticism, I want to leave you here with something of a teaser by highlighting two major ways that the early Church Fathers teach us about the earliest text of the NT and its transmission over the centuries.

1. They give us insight into the early text of the New Testament.

When we talk about the early Church Fathers, we are talking about Church leaders who lived and wrote around the 100s-400s AD. This fact alone makes their writings really important for New Testament textual criticism because this is precisely the time period where (1) we have the least number of New Testament manuscripts and (2) it is the most important period to know about to get back to the earliest NT text. These early Church Fathers fit squarely into this crucial gap. A careful and skilled handling of this material can give us a window into this murky but important period.

Here’s a prime example of how the Church Fathers help us understand the NT text in this period: In Luke 3:22,1 the majority of manuscripts, including the earliest manuscript we know of containing Luke 3:22 (P4, 100s-200s AD), have “You are my beloved Son, in you I am well pleased.” However, about 200 years later we find a Greek manuscript (5th-century Codex Bezae) with a different reading: “You are my Son, today I have begotten you.” If we’re only looking at Greek New Testament manuscripts, it looks like the first reading, in you I am well pleased, is quite a bit earlier than the other reading, today I have begotten you. We have no way of telling how much earlier than the 5th century the second reading came about. However: we also find out that Justin Martyr (100s AD), Clement of Alexandria (100s to 200s AD), Origen (100s to 200s AD) and several other early Church Fathers knew about the second reading: today I have begotten you. What appeared to be an obvious decision as to which reading is earlier is now a harder decision for scholars to make, largely because of the testimony of these early Church Fathers.

2. They talk about variants and show us how they dealt with them.

Not only can the early Church Fathers show us how early some New Testament readings were, but we even hear them sometimes wrestling with two or more different readings in the same passage. This is really valuable for us for many reasons, not least because this can show us that some textual differences were already in the manuscripts from really early times, and their approach to the variants can be instructive for how we think about differences in New Testament manuscripts.

For example, if you zoom back nearly 2,000 years to the 100’s AD, you will hear the Greek bishop Irenaeus of Lyons wrestling over which number was that of the Beast in Revelation: Is it 666 or 616? The manuscripts he knew about had either one or the other number, and this was only a few decades after Revelation was penned in the 90s AD!

He is convinced that the original number is 666 because (1) “all the good and old copies” have this number, (2) those who had seen John, the author of Revelation, say the number is 666, (3) and it is more logical that the number will be 666 instead of 616. He thinks that scribes accidentally put 616 instead of 666 because the Greek letter representing “6” looks a lot like the Greek letter for “1.” In other words, (and although current NT textual critics will not accept all of his arguments) Irenaeus is doing textual criticism even in the 100s AD!

Sometimes, early Church Fathers handle textual differences in ways that may surprise us. They did not see every variant as just as important as all the other variants, and they each had their own reasons why some variants were worth getting back to the original and why some were not worth it. However, they tended to share a common concern: the preservation of the core truths of Christianity. This means that when a Church Father knew of two variants in a passage that were both true of the message of the New Testament, they would sometimes let both readings stand together and even commend both readings.

For example, Origen of Alexandria (100s to 200s AD) was aware that some manuscripts read in Hebrews 2:9 that Christ died for everyone by the grace of God, while other manuscripts say that Christ died for everyone apart from God. He acknowledges that both variants are true about Christ and his work on the cross, but he does not seek to decide which variant is the original one. He instead weaves both together by commenting that Christ died for everyone except for God and that everyone is in need of God’s grace, but God is not in need of grace.2

Origen’s approach definitely differs from the way modern scholarship handles differences like this: Scholars today tend to try to get back to the earliest text of every place there is variation in the New Testament. And this is a great and good task. Yet these early Church leaders have something to teach Christians today: The Christian faith and the personal faith of Christians have historically been shaped by the New Testament (and Old Testament) message of Christ, not by the certainty one has of the original text in every word of the New Testament. Thankfully, the New Testament message of Christ has been faithfully passed down to this very day and is found in our Bibles across the globe. And we have the early Church Fathers to thank for helping preserve that message.

Today, we at CSNTM help carry on that task of faithfully passing down the text of this message to the next generation through digitizing New Testament manuscripts, educating all who will listen about the wonder of this NT text, and collaborating with scholars to shed even more light upon our understanding of this text.

- Thanks goes to Andrew Blaski for locating this example as seen in his “Myths about Patristics,” Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2019), 249. ↩︎

- Origen, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1-10, translated by Ronald E Heine (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2001), 1:255-256. ↩︎