By: Denis Salgado

The other day, I was reading about a mom who decided to remodel one of her kid’s bedrooms. The project involved the removal of ugly, floral wallpapers (do you remember those?). As this lady got to work and began to remove the wallpaper, she made an interesting discovery: beneath the floral wallpaper, there was another layer of paper. Instead of an ugly piece, however, the layer revealed a large vintage picture of Daisy Duck. Apparently, that wallpaper was issued about five decades ago! This mom now incorporated this vintage picture into the decoration of the room.

A similar phenomenon occurs with ancient manuscripts. We are not talking about removing physical layers of papyri or parchment necessarily but peeling off layers of text. And just as this mom got excited about discovering an older layer of wallpaper and was able to incorporate that vintage image into her remodeling project, New Testament textual scholars look for older layers of text in manuscripts that can be incorporated into our textual investigations, thus enriching our understanding of the transmission and use of the New Testament through the centuries. These additional layers of text are found in what manuscript specialists call palimpsests.

In this Manuscripts 101 post, we will discuss what a palimpsest is, some examples of New Testament palimpsests, and how scholars have used different technology to study palimpsested manuscripts.

What Is a Palimpsest?

A palimpsest is a manuscript whose text was erased, and another layer of text was written over the previous one. Basically, a palimpsest is a writing surface that has been reused for the purpose of writing.

Why did writers of the past reuse material? Some scholars believe they did so because papyrus and parchment were too expensive. Others say the reason was not related to finances but expediency. Especially in the case of long codices, it would be quicker to erase the text of one hundred leaves than to craft a brand-new codex of that size. Both explanations are legitimate.

The practice of erasing the text of a writing surface and reusing it for writing existed in the Greco-Roman society to some extent or another. For instance, from the Roman statesman Cicero’s letter to Trebatius on April 8th, 53 BCE, we learn that some of the letters Trebatius sent were palimpsests. Over a century later, the Greek writer Plutarch used the palimpsest in a negative way to portray a person who is unable to receive the commendable teachings of the philosophers—their corrupt habits and character are like stains that are hard to wash out.

When they mentioned palimpsests, the material Cicero and Plutarch had in mind was most likely erased and reused papyri. When it comes to the extant evidence for the New Testament, however, the palimpsests are made of parchment.

New Testament Palimpsest Manuscripts

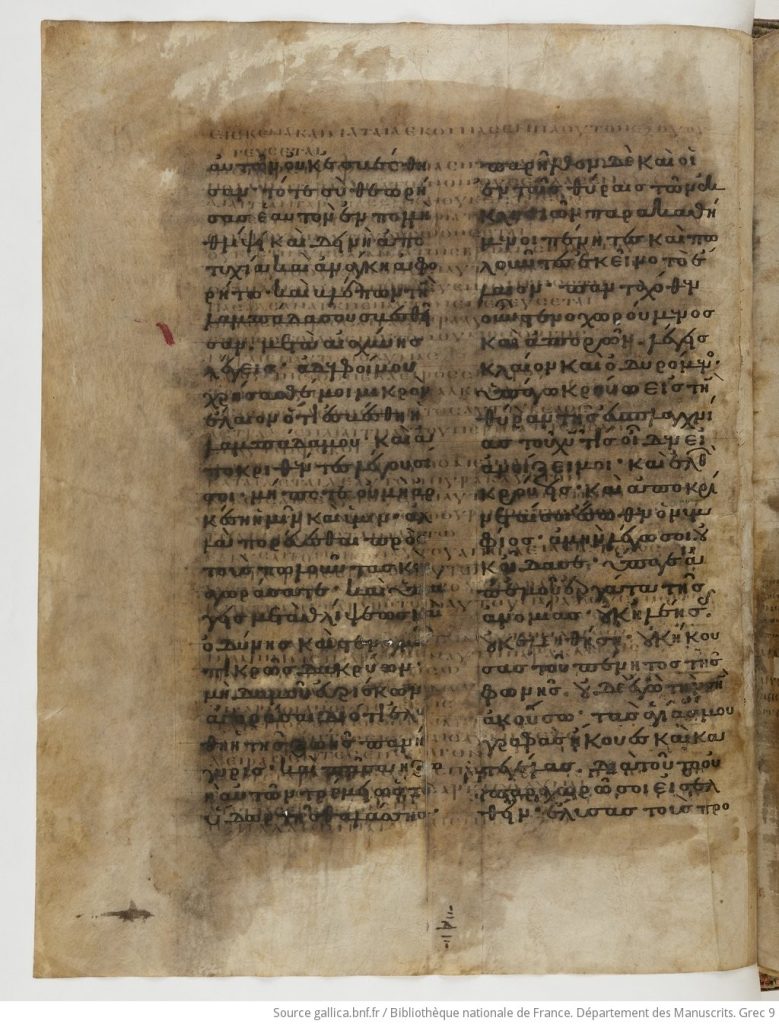

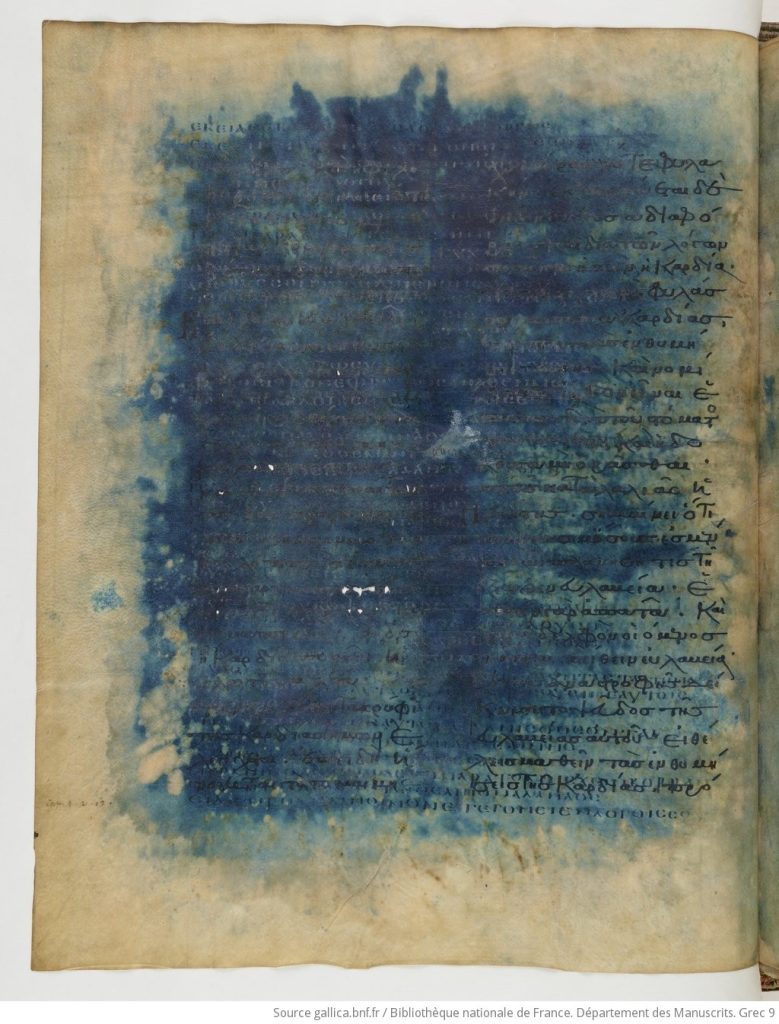

Most palimpsests were repurposed during the Medieval period. One of the oldest New Testament palimpsests, however, is Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (Paris, BnF, Gr. 9; GA 04), having a text dated to the fifth century on the first layer. This partially preserved codex once contained all the books of the New Testament (and the Old Testament). In the twelfth/thirteenth century, however, someone erased the first layer of the New Testament text originally written in the fifth century and reused the codex to write multiple tractates authored by St. Ephrem the Syrian (d. 4th cent.).

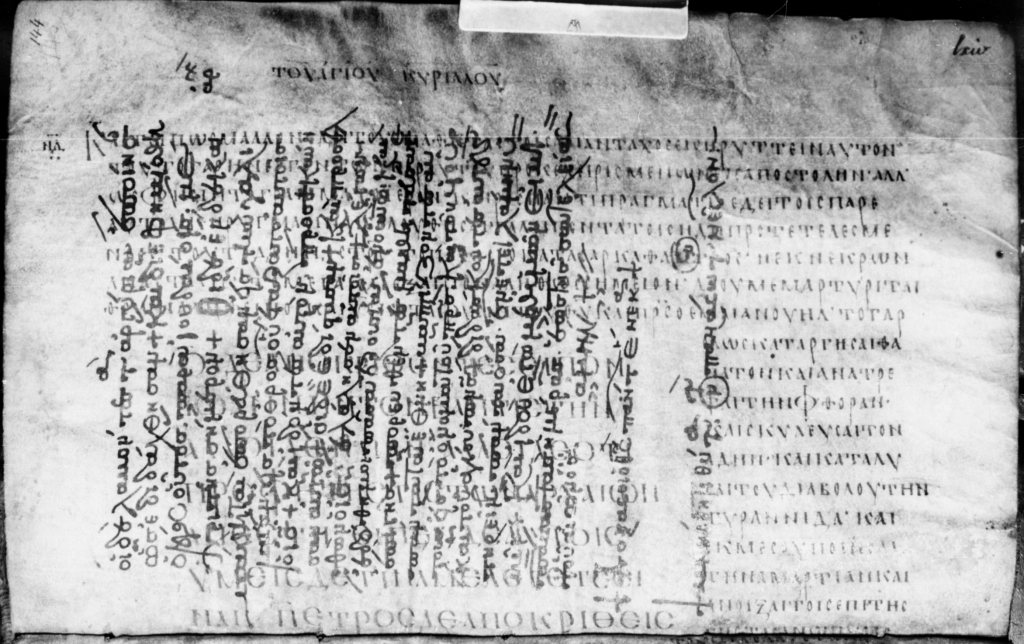

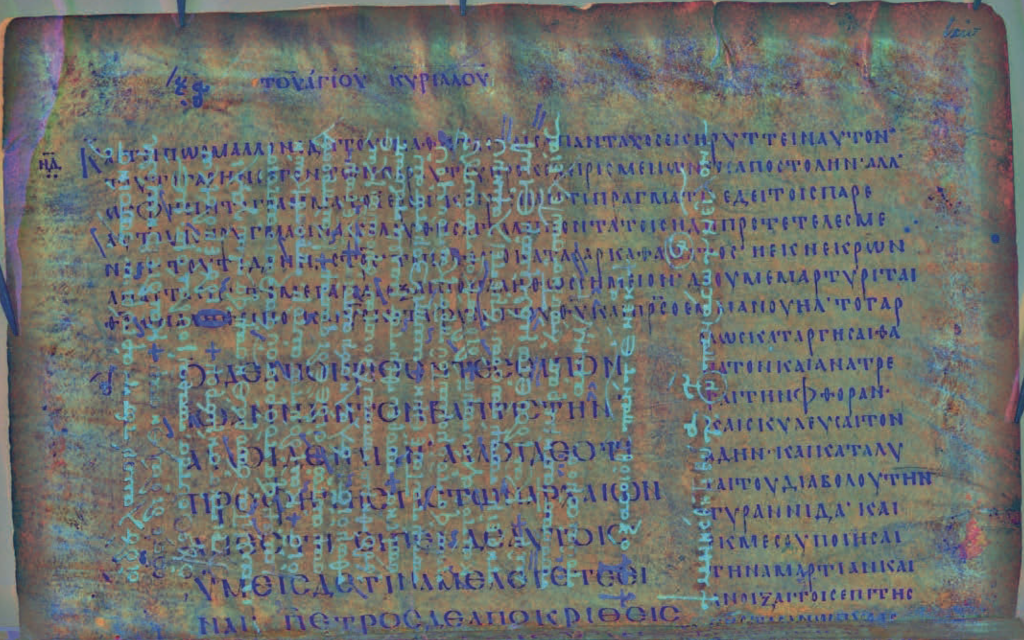

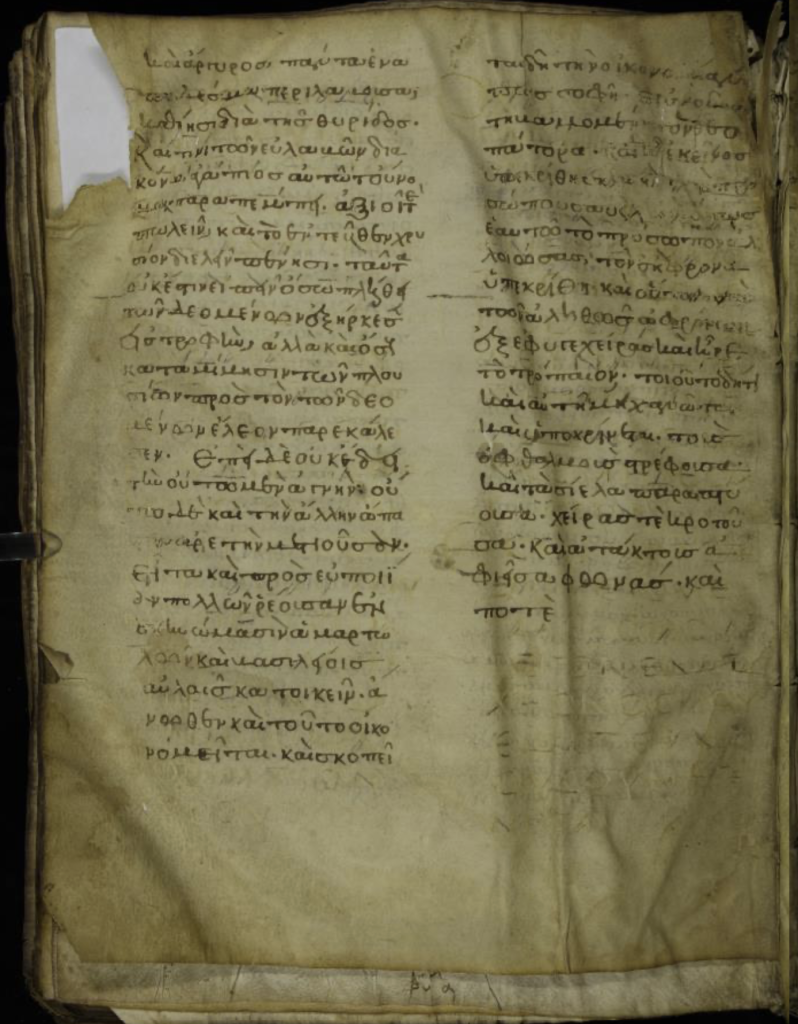

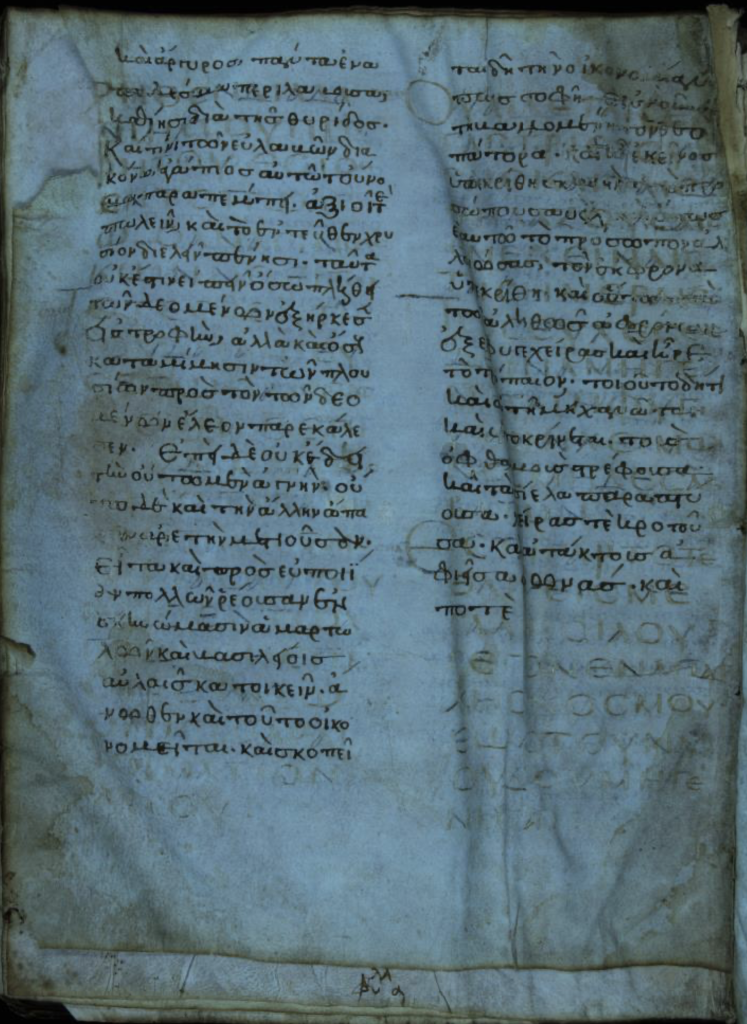

Another significant New Testament palimpsest is Codex Zacynthius (Cambridge, University Library, MS. Add. 10062; GA 040). The first layer of text is the Gospel of Luke with marginal commentary, written in majuscule script in the eighth century. This makes this document the earliest extant New Testament manuscript to preserve a commentary. In the twelfth century, the original text was erased to make space for a New Testament lectionary. The overtext is written in minuscule or cursive script. As shown in the image, the two layers of text run in different directions, perpendicular to one another. This manuscript was available to scholars only in microfilm format up until a few years ago.

When reviewing the microfilm images of Codex Zacynthius, it’s quite easy to read the text on the right side of the image because the overtext doesn’t extend to the bottom of the page and the first layer of text wasn’t thoroughly erased. On the other hand, deciphering the undertext on the left is quite challenging. Over the centuries New Testament scholars have employed different technology to aid in the task of uncovering the unseen text of a palimpsest.

Deciphering the Undertext

Miror quid in illa chartula fuerit, or “I wonder what was on that card,” wrote Cicero to his friend Trebatius in response to a collection of letters he had received from him. Basically, Cicero said: “I see you’ve been scraping the ink off papyrus leaves to write your letters. But I can’t help but wonder what was written on the leaves that you erased.” Cicero liked the tenor of Trebatius’ letters but seemed to disapprove of palimpsesting since the practice entails the loss of the papyrus leaf’s original text. In fact, Cicero’s real concern comes to light immediately after—he wondered if Trebatius wasn’t erasing Cicero’s own letters in order to reuse the writing surface!

Cicero is not alone in his concern. In the field of New Testament textual criticism, palimpsested manuscripts are valuable because they preserve multiple layers of history. In many cases, the first layer dates to Antiquity or Late Antiquity. But what was on that parchment first?

In the nineteenth century, scholars were captivated by the words veiled by the uppertext of Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus. Led by their curiosity—and ingenuity—they applied chemical reagents to reveal the undertext. The chemical reagents worked and some of the text became legible. At the same time, however, the method was destructive: it left dark green stains on the parchment, thus giving Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus its distinctive look.

When it comes to technology, we have come a long way since the mid-nineteenth century! Recently, a project carried out in the United Kingdom by the University of Birmingham and Cambridge University Library (click here for details and resources) investigated Codex Zacynthius in more detail. One of the first tasks was to reveal the undertext. Instead of applying destructive chemical reagents, however, the project employed a digital technology known as multi-spectral imaging (or MSI) to make the undertext legible. Thanks to this technology, we can now access texts hidden in plain sight and rediscover additional layers of Christian textual, exegetical, and liturgical tradition. This image shows the same page of Codex Zacynthius displayed above and can be contrasted with the quality of microfilm technology:

Similar MSI projects have been underway at multiple libraries with the goal of recovering the undertexts of palimpsests for research. Some projects include the Sinai Palimpsests Project (here) and the HMML Palimpsest Project (here).

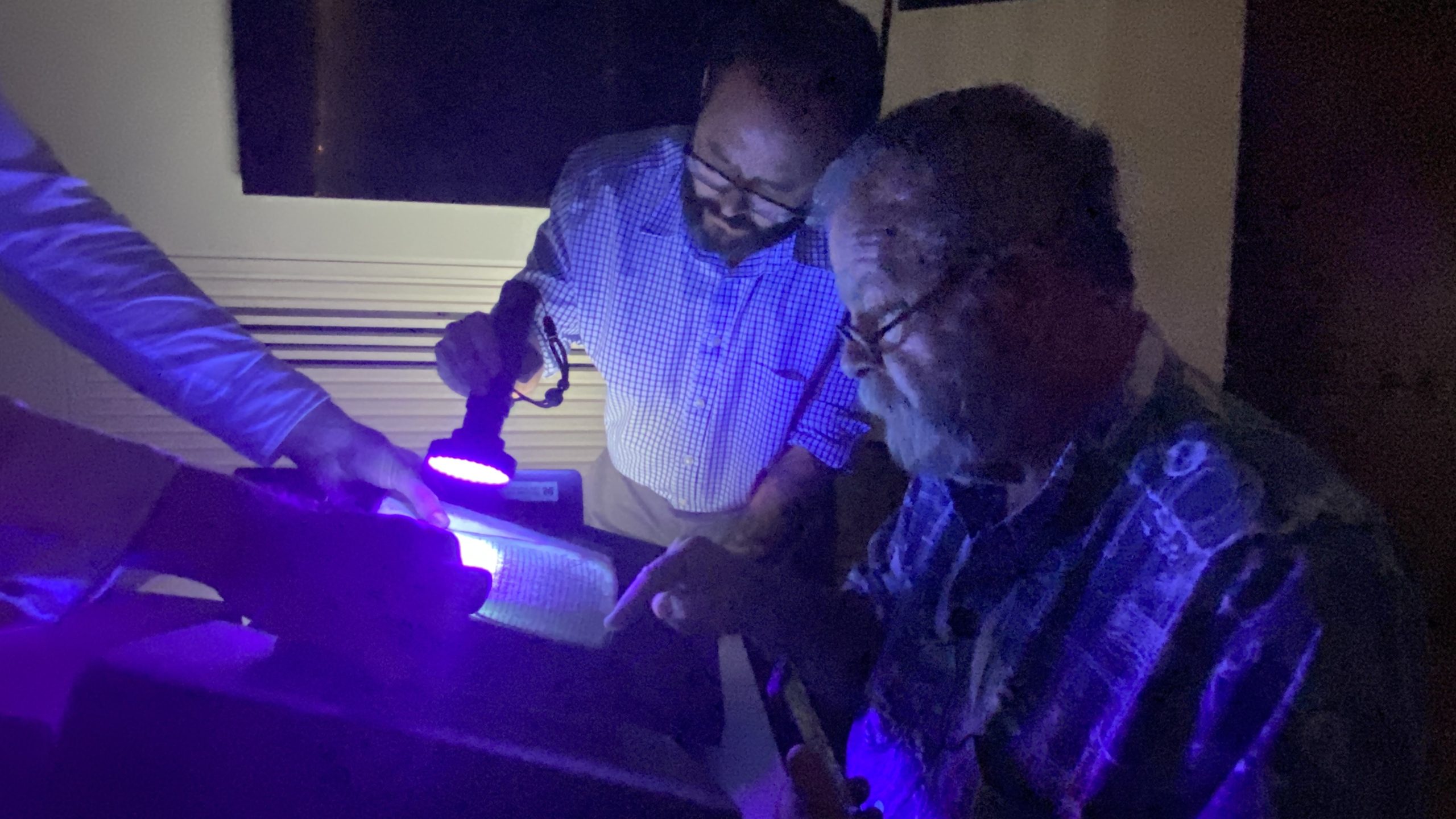

In 2015, the CSNTM digitized part of the collection of New Testament Greek manuscripts housed at the National Library of Greece, Athens. One of the documents is known as GA 094. This manuscript happened to be a palimpsest: the first layer is the text from Matthew 24.9–21, written in majuscule script, probably in the sixth century; the second layer is liturgical material written in cursive script. At first sight, it might be challenging to detect the presence of undertext.

If we suspect that a given leaf is a palimpsest, we shine ultraviolet light on it. The UV light immediately brings up the undertext otherwise difficult to detect under normal lighting. Once palimpsested leaves have been identified, they can then be marked for multi-spectral imaging.

Some of the libraries the CSNTM has worked with possess palimpsested manuscripts. The only way to find out what is written in the undertext is by performing multi-spectral imaging. Although the CSNTM currently owns one MSI device, we need to purchase more sophisticated equipment to perform more efficient and advanced imaging of palimpsests. If you would like to know more about palimpsests and the CSNTM’s needs to digitize them, get in touch with us!